A country choosing between alternatives technologies can be a difficult business at the best of times. This is because a given technology doesn’t usually do everything better than the alternative. It does some things better and other things not so well. Countries are often in different situations and therefore may have different views on the relative importance of particular features. Where it can get completely out of hand is when industrial advantage and industrial politics comes into play.

As it turned out getting the UK united behind one of the candidate technologies was relatively straight forward. Both operators preferred the Narrow band TDMA solution. Their view was heavily coloured by the transition problems they would face. Once the channels set aside for the GSM were all used, every time they wanted to expand the GSM system they would have to withdraw channels from the existing analogue system. Since there would be a lot of customers still on the existing analogue system for many years, the less channels they had to withdraw each time the better. The Narrow band TDMA system would therefore be less disruptive to customers than the Wide band TDMA system.

Most of UK industry came behind this choice since the Narrow band TDMA system looked easier to implement. They were starting further back and had more catching up to do. The UK test bed built around the Narrow band TDMA system was also a unifying factor. The only significant dissenting voice was GEC. They liked certain features in the Wide band TDMA system. David Tennant telephoned me. He said that they didn’t want to rock the boat and would accept the Narrow band TDMA choice. At the working level the consensus was complete.

Working with UK industry in this way and with government officials from the rest of Europe absorbed an enormous amount of my time. I had not paid any attention to the rest of Whitehall. That was nearly a very serious error.

The wake up call came via a phone call from Bernard Mallinder from Paris. It was early July 1986. “You’ve got trouble brewing old friend”. He had heard on the grapevine that there is a report circulating somewhere in Whitehall which slated the DTI for doing nothing on the new digital cellular radio technology in the face of the major French and German Government’s digital cellular radio initiative.

A week later there was a meeting between Alistair Macdonald and John Fairclough the new Chief Scientific Advisor to the Prime Minister. He’d come to talk about fibre optic communications that John viewed as the key to the new digital revolution. As the meeting broke up I asked him whether he would like to see what we were doing in the digital cellular radio field. He said he’d be delighted. A date in September was set.

Donald Cameron, one of my star performers for such occasions, was intending to go off to Tunis for a holiday in September. I twisted his arm to delay it. Robin Potter from British Telecom Research Laboratory had been told by his boss to attend a staff meeting on the day in question. I phoned his boss. “This is the third time we’ve tried to organise this staff meeting,” he growled. He finally relented. This went on until the team was assembled; including my final star performer Mike Pinches from Vodafone.

On the due date in September 1986 we had the narrowband TDMA test bed parked in a vehicle in Victoria street. John Fairclough turned up and received the five star treatment.

Over lunch John Fairclough became quite enthusiastic. He said that this was the first time anyone in Whitehall had given him such a presentation. As lunch progressed John Fairclough’s fertile imagination moved up a gear. “You know this has all the elements of a test case for European co-operation in high technology. If Europe can’t agree on this – what hope is there for other areas? What is needed is for the Prime Minister to throw GSM down in front of all the European Heads of State as a challenge for Europe. This would help to create a dimension above the narrow technical pre-occupations of the experts”. I choked on my well-done steak. I’d only intended to limit the damage of some official in the Cabinet Office whose knowledge on digital cellular radio had come from newspaper cuttings. “Industrial policy” was no longer politically correct and picking winners positively frowned upon. I was hoping to get away with both by creeping under the radar screen with a bit of help from a friendly DTI Minister or two.

My briefing effort with John Fairclough had come too late to stop the document Bernard had warned me about. Criticism of the DTI appeared in an ACARD report circulated by the Cabinet Office. Alastair Macdonald was irritated. He was determined to raise this at the next meeting with John Fairclough. This happened a week after the demonstration.

When the day arrived we sat in Alistair’s office waiting for John to arrive. The door opened and at first just a hand appeared and waved. A cheerful voice said “In case your wondering what this is I’m just throwing my hat in first”. A beaming face appeared. ” I owe you an apology Alistair.” said John, ” After the GSM test bed presentation I know the DTI is doing a splendid job.” This took us both aback.

Before we’d recovered John was seated and expanding on his idea on raising this with the Prime Minister.

“Don’t you think that the French and Germans might see this as being upstaged ?” asked Alastair. But, as chance would have it, we had just assumed the EU Presidency, the last of the big four countries to do so for some time. This gave us a well-accepted political locus in European affairs. The matter rested that John would raise it with the Prime Minister.

The officials in the Cabinet Office saw in John Fairclough, fresh from industry, as somebody in need of careful minding from the wily mandarins from the various Departments of State. “Watch it John ” one of them advised him “You’ll put the Prime Minister over the top of the trench to lead the charge and when she looks behind her…DTI will be nowhere to be seen. Where will that leave you? Just make sure Geoffrey Pattie has the support of the top industrialists before you raise it with the Prime Minister!”

The ball passed back into my lap.

Sometime later I met John on a flight back from Brussels and he told me a delightful story about his Cabinet Office minders. He’d just arrived and was brimming full of specific ideas to put to the Prime Minister. His minders warned him against putting specific ideas forward quite so soon. It would be much better to warm her up with a general appraisal of the situation, perhaps some very broad policy options. Having got her oriented in the right direction the ground would be fertile to put some of his more specific proposals. He reluctantly accepted the advice. Papers were commissioned from the Cabinet Office staff. They were about as general as they could get. They were submitted to the Prime Minister. He was called to a meeting to discuss the paper. As he entered Number 10 the Prime Minister was just coming down the stairs with his report in her hand. “Woffle John! Just woffle!” she said, “What I wanted is some specific ideas”. John told me that he could have sunk through the floor.

The condition set by the Cabinet Office was that Mr Pattie had to show that he had the support of the high level UK industrialists. He called a round table meeting.

In preparation Robert Priddle set up a meeting in mid October between Gerry Whent of Vodafone and John Carrington of British Telecom. It went well. My groundwork on the telephone with their support staff was productive. They both expressed enthusiasm. They agreed on the key points. A date in early November was fixed for the round table to be chaired by Mr Pattie.

Nothing was left to chance and my industry contacts were contacted to make sure compatible scripts were being put up to our respective masters. The day before the meeting Gerry Whent telephoned me. He just wanted to warn me that his managing director Ernie Harrison was particularly sensitive about his status relative to the Chairman of British Telecom, Ian Vallance. There was to be no question of the BT Chairman being treated as the senior man.

Next day I arrived at the meeting room 15 minutes early. I set out the name places with BT and Vodafone on the opposite side of the table from the Minister. I carefully moved the chairs so that the Minister’s chair was exactly opposite the space between the chairs of Ian Vallance and Ernie Harrison. A small detail perhaps but as Gerry Whent himself was to say to me later about Vodafone’s huge achievements – success is getting a thousand small details right.

The Minister’s round table meeting unfurled mostly accordingly to script. Mr Pattie got everyone at ease joking about not really being allowed to have industrial strategies any more. Ian Vallance was worried that co-operation might impede competition. Mr Pattie allayed his concern saying that talking of competition now was a bit like firing the starting gun when the runners were still in the changing room. One of the industrialists were worried about the 1991 date being promised for the start of service. I pointed out that a later date could put pressure on the French to ditch the digital cellular system in favour of an analogue system. Mr Pattie suggested that we all went along publicly with the 1991 date for international reasons but agreed to say inaudibly under our breadth “…. but very late 1991”.

Gerry Whent made a surprising departure from the agreed script proposing that the DTI should give £15 million to the two operators who in turn would fund prototype work with UK manufacturers. This brought a sharp rebuke from Sir James Blyth from Plessey. Plessey had learnt its lesson about accepting development money from the customer. This was the only discordant note.

A note was sent across to the Cabinet office recording the high-level industry commitment to GSM.

To my surprise Robert Priddle told me a few days later that the job was still not yet done. The Foreign Office had demanded “a strategy paper” for GSM but they had not elaborate what this was.

For the first time I sat down and thought through a complete industrial strategy for getting a pan European cellular system to market. The strategy would have four parallel planes of activity.

The top plane was the political level. The political will had to be generated to make it happen since markets were all out of phase across Europe. The French and German agreement had started the process. John Fairclough’s initiative with the Prime Minister would extend the process to the rest of Europe.

The second plane of activity was to get the commitment of the cellular radio operators to purchase the new networks and open a service on a common date. This was a crucial commercial agreement. Vague promises to open a service sometime were not good enough. My calculation was that at least three large markets had to come on stream at the same time to generate enough economies of scale. It would have to be a big enough bang to ignite the whole industrial supply chain from chips to large mobile telephone exchanges. The risks were too high to make it tenable for one or two countries to try and lift an immature technology all on their own.

The third plane of activity was the technical standardisation effort in GSM. Failure to agree a common technical standard would leave Europe with nothing.

Finally the fourth plane of activity was the industrialisation by industry. They needed to see a big enough market to motivate them to invest huge sums of money to make it happen.

It was essential for the strategy paper to begin by headlining how big the GSM opportunity was likely to be. The number of mobile phones was the critical data. No numbers existed over such a long time period. The industry itself was tearing up their forecasts every 12 months as growth kept exceeded expectations.

Projecting the future number of mobile phones in 1986 for the next 10 years was a slightly crazy undertaking. History was rich in pundits that had got forecasting spectacularly wrong. Like the mid-West newspaper in the US, just after Graham Bell had demonstrated the telephone, had the big vision that one day every town in America would have one.

It might have been easier to have plucked a number out of the air based on the golden rule of forecasting for political purposes – that it had to be a number big enough to make politicians take notice, not so fantastic that nobody believed it and far enough into the future so as not to be around.

In view of the stratosphere this paper seemed heading towards some real world quantification looked necessary. But where were the numbers to come from? The solution I chose was to use the best mobile penetration rates in Europe, which in 1986 came out of the Scandinavian countries, where one of them was touching 20%. This figure was applied right across the rest of Europe that was averaging under 2%. This number of customers was then multiplied by £200, a reasonable stab at the average selling price of a GSM phone over a 10-year period. A figure of £10 billion emerged and, by chance, met the golden rule. (Note: UK mobile penetration reached 20% by 1998).

It may surprise some that this was the first occasion when a classical industrial strategy had been done. But industrial strategies had gone quite out of fashion in Whitehall during this period. My boss Robert Priddle looked at it with an admiring comment – just like one of those French grand designs!

But it turned out that we had completely misunderstood what the Foreign Office had in mind in their use of the term “strategy”. What they wanted was a diplomatic plan of action, for example that Ambassador “Y” would see Minister “X” and so on. It was back to the drawing board.

When the Foreign Office version of the strategy was ready we went to a meeting at the Cabinet Office. Mr Williams was the Cabinet Office senior official preparing for the Heads of State Meeting. (He later became head of the Commission Services). Also at the meeting was Mr Braithwaite from the FCO who had just returned from being our Ambassador in Moscow.

As I sat down I put my briefcase by my feet. In the briefcase was my Excell mobile phone – key to my effort to base policy on hands-on experience. Mr Williams was in full flight when the wretched mobile phone started to ring. I tried to ignore it. It persisted. Now everyone was trying to ignore it. Oh God, I thought what do I do now. It is no good I’ll have to make the best of the situation. I got it out of my briefcase as casually as I could and answered it. As my conversation progressed the senior officials opposite me went from shock to horror to disbelief and finally to laughter.

It is my claim to the very dubious distinction of being the first person in the world whose personal mobile phone rang at the most embarrassing time. I may or may not have been the first but I certainly wasn’t the last.

On the matter in hand John Fairclough had done his job well. Mr Williams was in favour of the matter being raised at the summit.

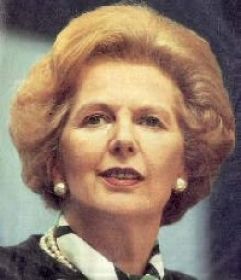

Figure 14 – Mrs Thatcher allows GSM on the EU political agenda providing it is uncontroversial

The reply from Mr Powell, her Private Secretary, said that the Prime Minister would agree provided she could be assured that it would not lead to discussion.

Back into my court.

A meeting of the Quadripartite partners in Paris was already in the diary. It got the job done without the need for ambassadors running around. The UK presidency was the last opportunity for any one of the four countries in the quadripartite agreement to get the matter raised at the EU Heads of State level. They were all in favour. This was reported back to the Cabinet Office.

The 1986 European Council in London under the UK Presidency was a two day affair. At the end came the communiqué. The serious newspapers next day reported all the things they saw of any importance, Aids, terrorism and a dozen other things but not a word about Europe’s future in mobile radio. The complete communiqué arrived a few days later. The pan European cellular radio system got three lines on page 44.

For all that work?

Despite my disappointment at its low visibility there was a pay off from Mrs Thatcher’s support in getting this onto the agenda of the EU Council.

It gave the Commission the confidence to table a draft Directive to require radio channels to be made available by all Member states specifically for the GSM system. It had got Sir John Fairclough fully on-side. Without doubt he, Alastair and Robert Priddle gave me the air-cover in Whitehall to pursue the DTI’s last great industrial policy strategy for two decades.

Equally important is that the discipline of fully developing an industrial strategy had given me the foresight to make a timely move later that was to prove crucial to the success of the pan European digital cellular radio initiative – the drawing up of the GSM MOU.

This only happened due to the mix-up with the Foreign Office over the word “strategy”. It had forced me into looking at the big picture and this had brought sharply into focus a missing vital component. A technical standard plus some fine political words would not alone create a service or the market for cellular radio products. My analysis had revealed that the key to successfully driving GSM to market was to harness of the combined procurement power of the mobile phone operators. This created the market at the service level, with the manufacturing opportunity being pulled along behind. It also aggregated all the purely national service areas across Europe to form a virtual European wide mobile radio service area for travellers. It was the big bang that would ignite a new digital mobile universe – a truly grand design!