Around 2007 3G became of age and mobile phone users, particularly those between 15 and 30 years old, found themselves in the midst of a tectonic change in the way they engage with the world around them. Every aspect in which we communicate and interact with the world around us changed in an even more fundamental way than was the case when the GSM revolution brought the mobile phone in reach of nearly everyone across the world. What was the technology genesis of 3G? Who brought to 3G a vision of a mobile world where everyone would be connected to an information universe, where pictures, videos, social networking and information sharing would become a fundamental part of everyday life?

Edwin Candy

Few have the privilege of being on the inside of such a technology revolution that lasted 20 years from inception to reality. Ed Candy is therefore in a fairly unique position to shed insights into this important piece of mobile history.

The era of conception

UMTS was conceived and progressed by the research community at a time when the feasibility of mass-market mobile car phones as opposed to business mobile car phones was only just being explored.

In 1987 personal mobile phones were the size of a house brick and cost over $1500 each. Office data systems for medium and large business were driven from huge central data processing centres with dumb terminals cabled back to the centres and personal computers were few and far between.

Mobile phone equipment network and subscriber prices meant that mobile was mainly only affordable by, and the prerogative of business users. The service capability and battery life was severely limited by the electronic components and technology available at that time and subscriber population penetration was less than ten percent in developed countries where a mobile service was available.

The predominantly state controlled telecommunications sector was rapidly being deregulated and privatized. The central European PTT administration Technical authority CEPT was being reformed into a broader European Standards body ETSI to include standards formulation for the new private sector operators and manufacturers.

Governments were considering if multiple licensees could be assigned in member states to encourage competition amongst mobile operators and PTT’s were divesting Mobile and Paging operations from their core fixed line activities to demonstrate that they were engaging in deregulation and the ITU the international telecommunications coordination body had commenced an initiative for a new international mobile specification and spectrum recommendation under the title FLMPTS (Future Land Mobile Phone Telecommunications Service).

The birth of a Mobile Phone research project – UMTS

In the late 80’s the European Commission established a part funded research program called RACE, an acronym for Research into Advanced Communications in Europe. It was “the carrot” part of a package of measures put forward by the European Commission to complete the Internal Market by 1991. The research proposal centred on the prevailing vision held by governments and industry around the world that the future of telecommunications networks would be a fibre optic connection to every home providing “super highways” of unlimited bandwidth.

The Philips Telecommunications Companies were engaged alongside other companies from across Europe in helping the Commission Officials to refine the program objectives. They had participated in the definition phase and hoped to be the beneficiaries of research funding.

In March 1987 Edwin Candy, who was International Systems Manager at Philips Radio Communications Systems in Cambridge England, was approached by the holding Philips Company and asked if he saw an opportunity for the radio business to benefit from some EU research funding. It was an optimistic “ask” as the RACE program from the start was sharply focused on research areas to support development of the fibre-to-the-home vision. The “call for proposals” documents contained no references to mobile telephony or any wireless solutions.

The next four weeks were to see an amazing convergence of ideas technology projections and visionary concepts.

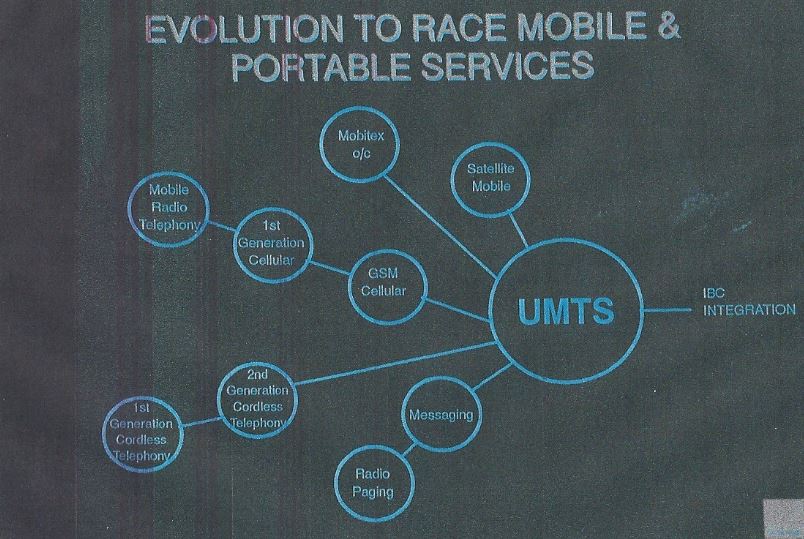

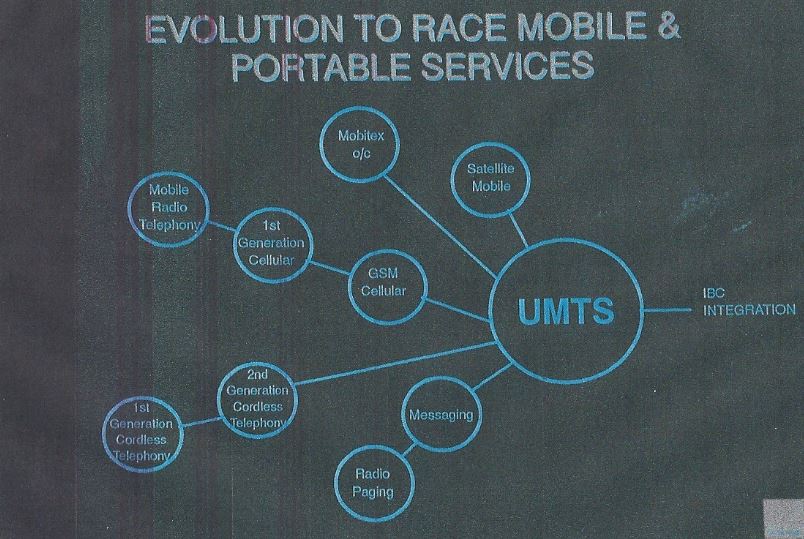

Figure 1 – UMTS road map

This journey began when Rod Gibson from Philips Research Laboratories in Redhill UK and Edwin Candy met together with their R&D engineers to consider whether a funded collaborative RACE program could benefit the research program at the Research Laboratories

They looked at how, in the future, very complex electronic functions and digital signal processing could be accommodated in relatively low cost digital integrated circuits, the advances in communication systems technologies and particularly how these could change the nature of mobile telephony systems and services over the next ten years. These could lead to a Universal Telecommunication System.

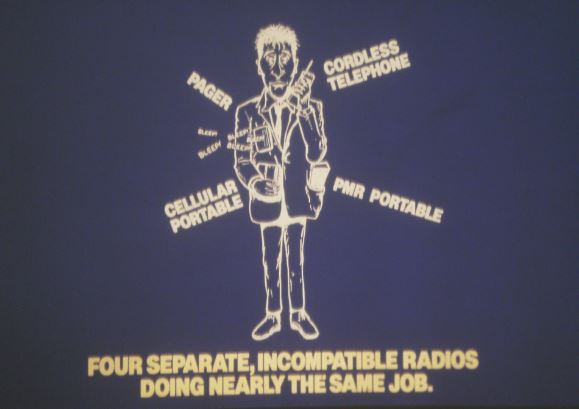

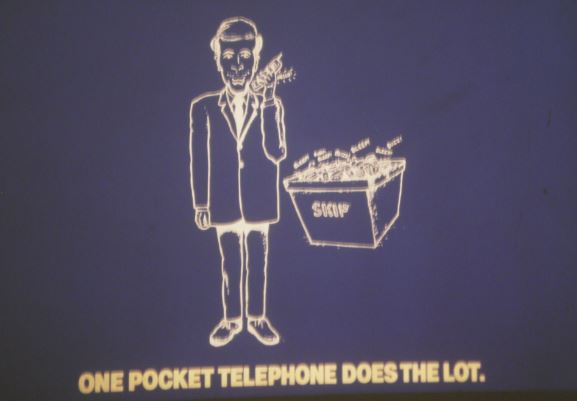

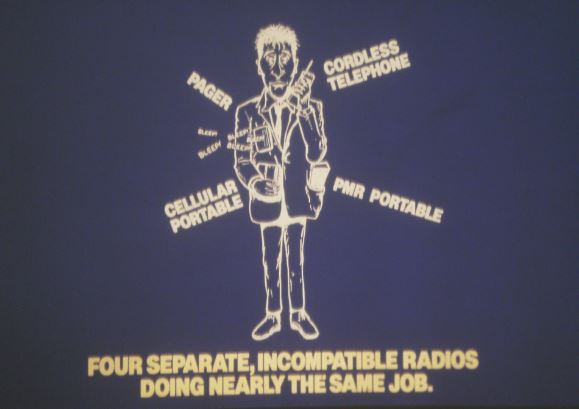

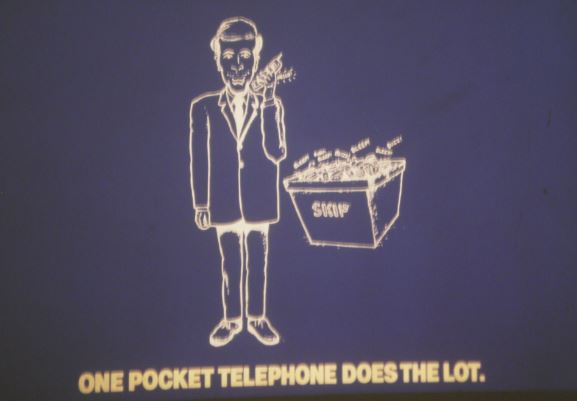

The emerging goal was encapsulated in two cartoons with the caption ” one pocket telephone does the lot

Fig 2 & 3 – How the cartoonists saw it

Philips at that time were researching technologies which could be used to increase the capabilities of low power digital integrated circuits which could be used for portable equipment. Their experience as one of the world’s largest manufacturers of consumer electronics products provided a rich insight into the possibility that highly complex personalized phones that could be developed using new digital techniques and components and the impact that scale would have on the price.

Already it was possible to see the impact large-scale integration would have on the early GSM products and understand how equipment pricing would be driven down with the scale afforded by a Europe wide market for mobile telephones.

Over the next month Ed and Rod began to formulate an embryo of a very bold initiative. Within days young R&D engineers from across Philips, including Gerard MacNamee and Sunil Vadgama, were transferred to Cambridge to look at the feasibility for a revolutionary new mobile system, which they called UMTS – Universal Telecommunication System. It was to be a network, which would provide affordable pocket mobile telephony and video at 2 Mb/s for everyone.

A Gap in the Vision

Although the UMTS Vision was surprisingly accurate, and recognized the need for a high rate data channel to and from mobile and the need to connect to connect to computers and data centres, it did not see foresee the possibility of a huge data network of equivalent in size and reach of the telephone. Nor did it see the dependence by today’s society on connection to the Internet. In fact the World Wide Web was not invented until 1989 and the Apple iPhone did not arrive until 2007.

In many ways the later development of the Internet and web services simplified and reduced the cost development of UMTS and provided an unimaginable diversity of services and richness of experience, which underpins mobile services today. It also meant that in the later stages of development the data aspects of UMTS were available as UMTS services.

The Collaborators

In April 1987 a two-day seminar and meeting was organized at Philips Research Laboratories in Redhill to consider if a collaborative program could be established under the rules of the RACE programme. An invitation was extended to equipment and component manufacturers, telecom operators and universities across Europe.

Figure 4 – Representatives from 9 European manufacturers descend on the Philips Research Labs in Redhill, England

Participants included manufacturers Ericsson, Nokia, Alcatel, Bosch, Thompson, Thorn EMI, Plessey Roke Manor Research, GEC Marconi and of course Philips. There were representatives from Universities including Karlsruhe, Strathclyde and Bradford. British Telecom and the Greek operator OTE represented the operator community in both fixed and mobile.

Ed Candy and Rod Gibson set out a research program for a UMTS network and a consortium management structure for such a collaborative program. The aim was to define a network and technology, which would lead to a single set of standards that would be used to create not just a European but world network and market. At its heart was the vision of the UMTS service in fifteen years’ time. From this flowed the major technical challenges and the identification of research domains needed to achieve a UMTS network. Attendees were invited to describe their research programs in mobile and consider how these could contribute to UMTS. A series of workshops were organized to allow participants consider if these diverse capabilities could indeed create UMTS.

In order to consider synchronization between the multitude of independent research activities and the financial constraints, participants were invited to set out current and future research work areas in mobile and committed resources. This process allowed visibility of mobile research across the industry and to see if a UMTS program could be constructed from these activities. It also allowed identification of challenge areas where new work would have to be commissioned.

Research is significant financial commitment by organizations, so in addition to the technical challenge the benefits from a part funded program had to be considered in terms of available resources and be financially viable. To gain acceptance from each of the participating organizations, the program would have to enhance and complement their own activities.

Overnight between the two days of meetings Ed and Rod tabulated and matched the respective programs and established that the individual research activities were surprisingly complementary. Where research topics overlapped or where tasks were under resourced, tasks and resources were interchanged between participants.

The outcome exceeded everyone’s wildest expectations. By the close of the meeting the headline structure of the UMTS program had been completed and participants left with the task of obtaining agreement for participation from their organizations. UMTS was underway.

This in itself was an extraordinary achievement between enterprises, which for the most part were in fierce competition in their respective fields. What helped to solidify this spirit of cooperation is that the meetings exposed that the task was well beyond any individual organization in terms of resources and technical capability but it could be achieved as an Industrial group. It validated the European Commission’s belief that collaborative pre-competitive R&D was essential for European industry to stay in the global race.

The RACE UMTS submission

Selection of research proposals for funding is a very competitive process. The total sum of the bids always exceeds the money available several times over. The Commission Officials ran a very transparent process. The projects needed to comply with a wide landscape of requirements over and above technical excellence. They needed to encompass stakeholders from education and businesses of varying size from different regions. The participants had to be able to ultimately exploit the research. But there was no escape from politics. The funds need to be distributed proportionately across Member States.

Ed Candy established a team in Cambridge to prepare and submit the program. The composition of the work programs was refined again and again as available resources, capabilities, and respective costs were identified and confirmed.

PA Consulting were selected to prepare the submission and to assemble the work packages deliverables and work items together with the articulation of the benefits that UMTS would bring. Graham Maille and Geoff Vincent from PA joined the team and set about preparing the extensive documentation required for such a large consortium.

It became clear at an early stage that there would be over twenty partners in the program and that funding of around £35 million would be needed for the first phase. As the finance technical and administrative process continued a number of new partners emerged. Fortunately these organizations brought additional skills and a very robust and feasible technical program took shape.

At that time telephones either connected to a fixed point or to a vehicle on the move. Expensive over-weight transportable phones were still a novelty. The idea that everyone could be connected to the telephone network with a pocket phone and even more far-fetched was that people would exchange pictures. The submission had to address objections from sceptical evaluators.

In addition to outlining the technical challenge much explanation and study was required to justify that, by 2003, it would be possible for almost everyone to have a handheld phone. Moreover, it needed, to justify, that by 2003, more than 50% of telephone communication would take place between people not places. This was an essential tenant of the program as a scale of this order was fundamental to achieving affordability. The phrase “people want to talk to people rather than places” became the rallying call of those involved in the project. Even the RACE Mobile program Logo featured a stylised head high lighting mouth ears and eyes.

There were many views expressed in the 1980’s that it was unlikely that people would find it acceptable to make telephone calls in the street. But we know now that mobile phone behaviour in 1987 was a reflection of capability of systems and equipment not in response to societal imperatives. The change in mobile phone user behaviour over 15 years is remarkable. The submission also encapsulated the principal depicted in the early cartoons that a single device could replace a multitude of personal devices including paging and a camera.

The submission introduced the concept of successive generations of mobile services. Analogue systems such as the as AMPs, Germany’s MATS E and the Nordic NMT were considered as 1st Generation. GSM as a digital technology solution to provide Europe with a Pan European mobile telephone service where users could roam without complication amongst member states was considered as 2nd generation. UMTS with it “broadband” mass-market capability was represented as 3rd Generation.

The final UMTS submission to the RACE management team proposed a consortium of 25 partners for a £39 million 50% funded program.

Figure 5 – RACE Mobile Logo

Scandinavian companies had yet to join the common market but an agreement existed with the European Commission, which allowed them to participate as EFTA members but without funding’ Both Ericsson and Nokia played a fundamental part in the creation of the program and indeed their contribution to UMTS in the early days was key to the success of the program.

The Award

The UMTS submission team had every reason to be optimistic as the entries were analysed. They got feedback that the submission had gained recognition for its technical quality and leadership. They were optimistic that the submission would be recognized as having strategic importance in the context of European society and Industrial objectives.

The Group were stunned when a matter of days before the final decision in August 1987 rumours circulated that less than 5 million ECU (pre-Euro name to the European Currency Unit) had been ear-marked. An even worse rumour followed that the UMTS program was likely to be rejected entirely by the RACE Management Committee. Some Member States were concerned that the program would compromise the fledgling GSM initiative, not recognising that this UMTS research project was a program looking fifteen years ahead. Rather than threatening European industry it would provide protection for future industrial activity against a highly competitive mobile technical capability developing in Asia and the US. But the reality was that the knife was being wielded to get the programme expenditure to fit the available budget. The UMTS vision had nothing to do with the consensus vision of a fibre optic connection to every home. This made it an obvious target for the axe.

Members of the consortium were mobilized to lobby their national governments. The feedback was not good. The intentions of the RACE management committee members had been well telegraphed and the final vote within a day would merely underwrite the Commission decisions, on budgetary grounds, to axe the UMTS project. The position of Member States (represented on the Management Committee) was driven by many factors. For example the UK position was driven by a row behind the scenes between the Treasury (who did not want any EU money spent on R&D), Cabinet Office (who were trying to limit the scope of the program to limit its cost) and DTI (who were responding to industry pressures).

As a very last ditch effort an urgent meeting was sought with Roland Huber the Director DG XII who was responsible for the EU Research programs. But nobody knew him personally and it was exceptionally difficult to get meetings with such a very busy senior person. It was a secretary who came to the rescue. She simply picked up a phone and called the secretary of Roland Huber. Who knows what was said between them but a meeting was arranged at very short notice. Ed Candy and Rod Gibson were on the next plane to Brussels to try to convince Roland of the importance of the UMTS program and seek his intervention.

Ed gave the performance of his life to a sceptical Roland Huber…himself a passionate believer in the fibre to the home vision. After a long and intensive debate Roland agreed that the UMTS inclusion in the program should be reconsidered.

The next day he agreed that, although the full funding could not be granted, there was a possibility of a last minute submission failure which would allow a first phase of 14 mECU to be funded. However that depended on Roland single-headedly altering the view of the RACE management committee before the vote later in the day. UMTS scraped through by a margin of two votes that afternoon.

The world owes much to that secretary…

RACE UMTS Project R1043 came into life

It was a hard won success. Roland Huber was good to his word and the program was funded to Euro 14 mECU, then 28 mECU the next year. The UMTS program continued as a flagship program in the following RACE II program and the validation program called ACTS. By 1996 over 200 mECU had been spent jointly by Member States and the industry on UMTS research and platform validation. The Member States were to get all of that money back from the 3G spectrum auctions that came later, a twist of fate that was less kind to the European manufacturing industry.

The ITU and FLMPTS

Coincidently with the creation of the UMTS Race research bid the International Telecommunications Union Radio (ITU-R) recommendation working group were taking recommendations on next generation mobile specifications under the Chairmanship of a Canadian Mike Callender. The program was titled Future Land Mobile public Telephone service (FLMPTS). It was primarily directed at identifying and producing recommendations for the harmonization of mobile spectrum allocations across the world. This meant that by the time the UMTS research phase some general principles of spectrum harmonization would be recognized by Spectrum administrator across the World.

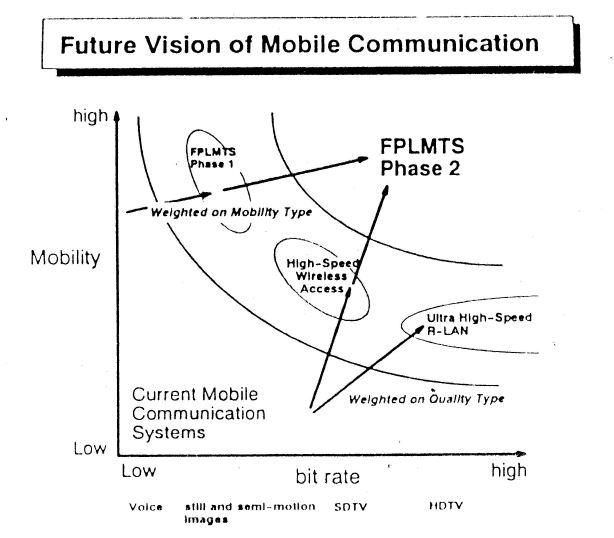

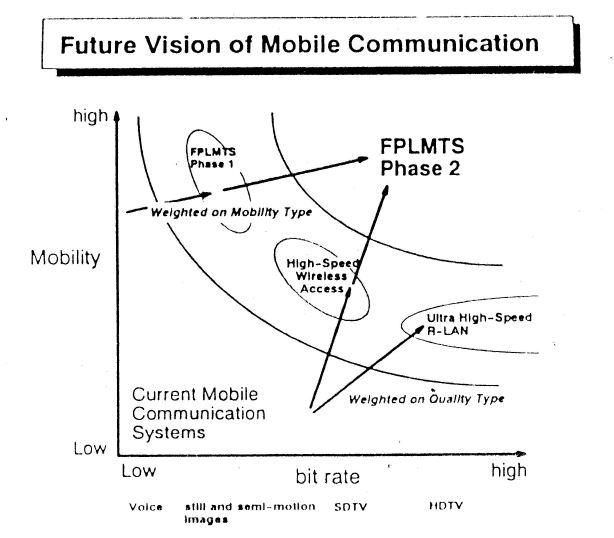

Figure 6 – Diagram of Future Vision of Mobile Communication

The ITU working groups were also working on the challenge of increasing the data through put of mobile systems whilst maintaining mobility.

The real work begins

By the end of 1987, the Commission contracts for the consortium members had been finalized under the guidance of Commission Official Spirious Konidarious. The Commission contract coordinator for R1043 was Adrian Melis. Key staff were selected by the consortium partners and the program the commenced with an inaugural meeting of representatives from each of the twenty five-member consortium in Cambridge at the Arundel House Hotel in January 1988

With the project underway Philips appointed Tom Parrot as Program Manager. Edwin Candy had moved on to take on a new role as Technical Director for the Telepoint Joint Venture between Philips, Barclays Bank, and Shell.

It was now down to the research engineers to work through each of the challenges and provide solutions. As well as individual technical tasks, an architecture or systems design work package had been established with Gerard MacNamee as its leader. As well as addressing some of the most complex systems issues it had the additional responsibility to ensure that technical solutions were compatible with the overall program.

Great progress was made by 1992 with successive enhancements to the program and increased funding granted at each stage.

Opposition continues

Detractors continued to argue against the program, but, as it remained in the research arena where results were highly valued, the opposition had little impact. The program gained credibility. Research deliverables, particularly in the radio area, were used to improve GSM including the early propagation studies into the 1800MHz band. This contributed directly to the development of the DTI’s successful ‘Phones on the Move’ initiative that led to the specification of DCS1800. Stephen Temple, Chairman of the ETSI Technical Assembly, ensured that this became part of the broader GSM specification. One of the by-products of the program was the transfer of technology and innovation to the strengthen GSM. Over the research period, the technical advances, which allowed for the possibility for UMTS, were used enhanced GSM terminals and network equipment alike. These advances played a part in GSM’s migration to a mass market and the almost universal adoption of the standard across the world.

Opposition however grew as the possibility of industrial exploitation drew closer. The great fear was that GSM would be displaced. In reality GSM would only be displaced by its own limits. The improvements in radio technology, allowing higher frequency bands to be used, would open up a vacuum for rival industrial initiatives to fill from other parts of the world. But those still struggling to get GSM off the ground could not see so far ahead.

Industrial Exploitation

With the completion of the RACE II UMTS research program in 1992 the Commission were keen to see the work progress toward industrial exploitation. The first step was platform validation. A UMTS validation program “FRAMES, under the ACTS program was commissioned to build two platforms using candidate multiplexing techniques one trialling Advanced Time Division Multiplexing, ATDMA and the other, Wideband Code Division Multiplexing WCDMA. Both techniques were advances of proven 2G narrow band-multiplexing systems.

Ultimately both systems performed to expectations so it was down political and industrial competition for the choice.

The UMTS Task Force

With the UMTS program drawing to a close and the final concertation seminars concluding, the process to bring UMTS to maturity was still unclear and the bridge from research to reality uncertain.

The issue was discussed following a concertation meeting in Brussels in March 1996 between Jo Da Silva from the Commission, Bosco Fernandes from Siemens, Edwin Candy who was now Technology Director at Orange and Robert Swain from British Telecom’s Martlesham Research Laboratories. It was agreed that the stakeholders from the Mobile Industry needed to be brought together so that the spectrum, regulatory and standards processes could be set in progress. A task force was agreed and commenced in April 1996. Members were selected representing Manufacturers, the UMTS research program, Operators, Commission officials, industry bodies and the European standards body ETSI:

| Name |

Organisation |

| K Birmqfti |

ETNO-FM |

| E Buitenwerf |

KPN |

| E Candy |

Hutchison Orange |

| A Geiss |

ERO |

| J Desplanque |

France Telecom |

| P Dupuis |

ETSI TC SMG |

| B Eylert |

DeTeMobil |

| B Femandes |

MPLA |

| F Hillebrand |

GSM-MoU |

| L Koolen |

DGXIII-A |

| K Lorentzen |

K Lorentzen |

| U Lori |

ETNO-MC |

| J-Y Montfort |

ETO |

| M Nilsson |

Ericsson |

| P Olanders |

DECT Operations Group |

| J Rapeli |

ETST-SMG5 |

| J da Silva |

DCXIII-B |

| R S Swain |

British Telecom |

| E Vallström |

Nokia Telecommunications |

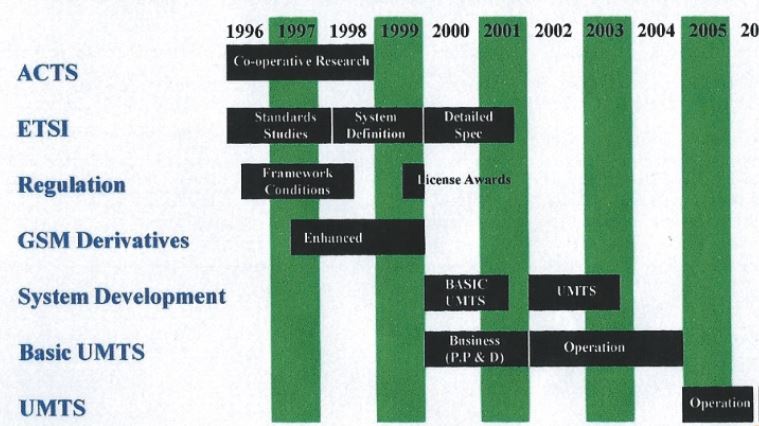

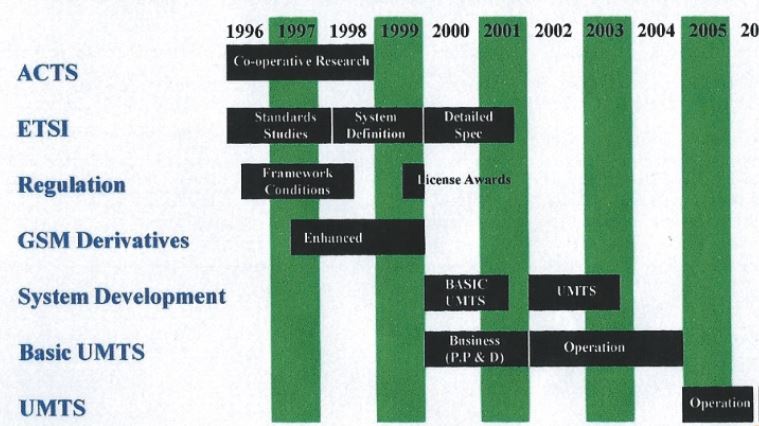

By August 1996 a task force report had been published with a timetable setting out the steps for commercial UMTS deployment in 2003, draft European council directives for spectrum outlined and a proposal for a UMTS Forum to drive the progress of UMTS across the mobile industry.

Fig 7 – UMTS commercial launch timetable.

The UMTS Task force report set out a series of recommendations for the establishment of UMTS networks across Europe:

- The development and specification of the UMTS such that it offers true 3rd-Generation services and system.

- UMTS standards must be open to global network operators and manufacturers

- UMTS will offer a path from existing 2nd-generation digital systems, GSM900, DCSI800 and DECT.

- Basic UMTS, for broad-band speeds up to 2Mbls, should be available in 2002.

- Full UMTS services and systems for mass-market services in 2005.

- GSM900, DCSl800 and DECT should be enhanced to achieve their full individual and combinational commercial potential.

- UMTS regulatory framework (services and spectrum) must be defined by the end of 1997 to reduce the risks and uncertainties for the telecommunications industry and thereby stimulate the required investment.

- Additional spectrum (estimated at 2×180 MHz) must be made available by 2008 to allow the UMTS vision to prosper in the mass market.

The formation of the UMTS Forum

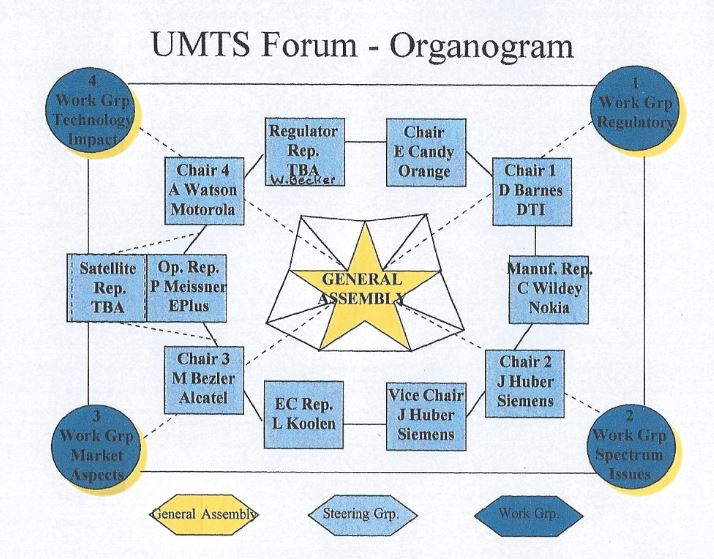

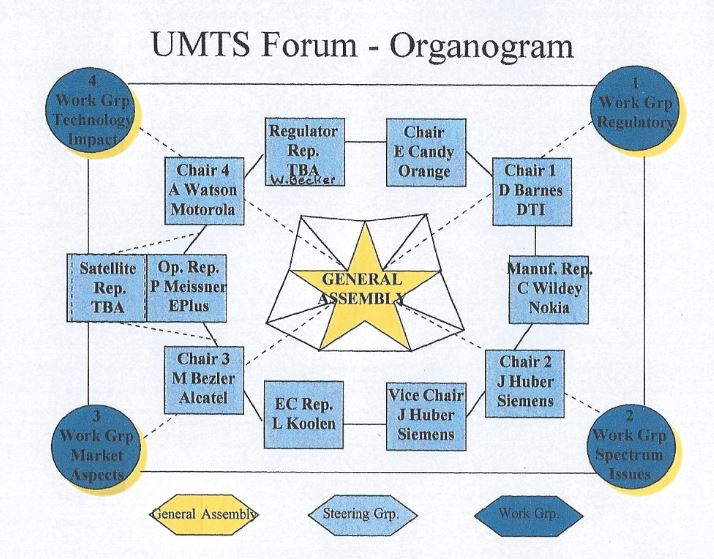

In August 1994 the UMTS Forum, led by Ed Candy, was set-up. By December 1996 the Forum was established as a legal entity with secretariat funded by the membership. A Management team representing Regulators, Operators, Market strategies, and Technologies with Edwin Candy elected as its first chairman.

Fig 8 – Signing of UMTS incorporation by the Inaugural chairman Ed candy

The forum went on to play a crucial part in the introduction of UMTS. The structure of the forum was unique. The close links between the representatives of governments across the EU and the UMTS forum with its representation across the entire industry and allowed issues to be resolved in a collaborative environment. Chris Whiley volunteered to be first secretary of the UMTS Forum.

Fig 9 Photo Forum Incorporation chairman Ed candy and Chris Whiley Secretary

Figure 10 – Organisation of the UMTS Forum

Fig 11 – Representatives at the Inauguration of the UMTS forum.

The UMTS standards

The UMTS task force had recognized early on that standards for UMTS needed to be progresses promptly and ETSI was approached to do the job. This would normally have involved setting up a new group for the task. However the apprehension that UMTS was a threat remained amongst many in the GSM community. The proposal to establish standards group for UMTS in ETSI was vigorously opposed. Some argued that the fledging GPRS packet evolution of GSM would be sufficient for data services and that UMTS would not be needed. Stephen Temple, the ETSI Technical Assembly Chairman, proposed a compromise that would place the further GSM standardisation work and the new work on the UMTS standard under the same SMG Chairman Philippe Dupuis. This allowed an early start to UMTS standardisation and cementing UMTS as a logical revolutionary progression from GSM.

Initially UMTS standards work was limited to the attachment of a UMTS radio Air interface to a GSM core but work was already underway to a strengthening of the GSM packet core network. Ultimately all the parts of the GSM network were redefined in such a way that platforms purchased as the GSM networks were upgraded to meet capacity would be equally able to support the functionality demanded by UMTS.

Industrial might

Europe was not alone in researching and developing wide band mobile systems, and a number of corporations held lucrative patent portfolios for mobile technology. Similarly Governments were realizing the economic benefits from a vibrant mobile manufacturing sector. Stakes in mobile were high. Digital GSM had deposed the analogue US AMPS as the preferred cellular system across the world. Japan was also looking to leverage its superiority in consumer electronics into the volume mobile sector.

This clash of interests led to a battle for the selection of the chosen radio technology for a global UMTS air-interface standard. Two dominant and viable technologies emerged from the UMTS program: ATMDA and WCDMA. In the end the selection became a political choice as Europe supported the ATDMA system, Japan supported WCDMA and the US supported a narrower version of WCDMA in an effort to leverage and promote their 2G CDMA system produced by Qualcomm as a wideband solution.

In an effort to secure a 3G UMTS world standard ETSI encouraged the formation of a Partnership Standards body (3GPP) to encompass standards interests wider than Europe and a series of inter government meetings between the US Japan and Europe (under the abbreviation FAMOUS) took place 1996 and 1997. Unfortunately the emerging consensus between Europe and Japan on a common Air interface standard was not supported by the US and the utopia of a world standard faltered

In recognition of the strength of Asian consumer electronics and the wish of European manufacturers to secure Asian markets a decision to adopt the WCDMA interface preferred by Japan was chosen by ETSI for UMTS. This was sufficient for it to be accepted by 3GPP. In an effort to sustain at least a continuing global dialogue on standards the 3GPP formed two specifications, one for the European-Japanese axis and the other for the US narrower-band version of CDMA. Ultimately these versions were merged in 2004 as WCDMA became the preferred solution.

Finally the first version of the UMTS specification emerged in 1999 as Release 1999 or R99 for short. This first version specified a radio data carrier rate of 384 kb/s. This fell well short of the original target of 2 Mb/s set out in the original vision, but at least a high bandwidth service had been specified and manufacturers were committed to supplying equipment.

A 2003 3G commercial launch

In March 2003 the first 3G UMTS WCDMA networks operated by the “3” Group owned by Hutchison Whampoa commenced commercial service in the UK and Italy. As had happened with Mannesmann and GSM, it fell to a new entrant to take a full share of the teething pains of bringing a revolutionary new technology to market. The Chief Technology Officer for the UK “3” mobile operator at this time was Ed Candy. He deserved more than anyone the satisfaction that the UMTS service had launched almost precisely to the date predicted at the conception in 1987 and again by the UMTS task force report in 1996. Whilst its data rate was only a third of the target of 2 Mb/s, advances in video processing and compression allowed the transmission of useful video services right from the date of launch. 3GPP grew in global stature as it relentlessly went on to enhance the packet service specification to plug this missing piece of the vision. The High Speed Data Packet Access (HSDPA, and HSPA) very quickly followed pushing the gross carrier throughputs toward 7.2 Mb/s, then 14.4 Mb/s, 21.8 Mb/s and onwards.

By 2006 3G networks were rolling out the high-speed versions of HSPA and operators were offering data rates on mobile phones, which were comparable with rate available from domestic last mile fixed services at that time. It was all “just in time” to take the brunt of the user data explosion ignited by the arrival of the Apple iPhone in 2007.

As soon as user terminals provided universal and fast connection to the Internet data volumes across the mobile networks climbed spectacularly. Between January and December 2007 UK operator H3G saw their data throughput change from 90% Voice and l0% Data to 10% Voice and 90% Data and with a 15% increase of Voice. The data explosion had arrived. The world was soon crying out for the next mobile technology generation.

3G (or UMTS) was a revolution. But it was not the only revolution. Economists had taken an interest in the value of radio spectrum. They persuaded Governments that auctioning the spectrum would not only raise for them a lot of money but came up with a theory that an auction would get spectrum into the hands of those who would make the most productive use of it. The 3G auctions spun out of control and not only created serious damage to Europe’s telecommunications sector but seriously set back the benefits of the 3G technology revolution. READ HOW THIS 3G AUCTION DISASTER HAPPENED…Click on this link