A Short History of the 5G Pioneer Bands

A personal account by Prof Stephen Temple CBE, Visiting Professor at the University of Surrey 5G Innovation Centre and the creator of the concept of the “5G Pioneer Band”.

“A concept that was to completely change the direction of 5G in Europe”

A successful cellular mobile technology revolution needs a careful matching of:

- Market need

- Internationally standardised technology

- Regulatory Framework

- Harmonised spectrum bands.

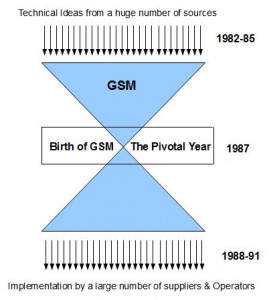

The secret of the huge success of GSM had been to give careful attention to getting the mix of these four ingredients right. Whilst the world has changed, technology has advanced and there are many new challenges ahead, the formula remains basically sound for the success of 5G.

By 2015 the global supply industry had came to a collective view that the band at 28 GHz was to be the “harmonised spectrum band” for the new internationally standardised 5G technology to be rolled out from 2020. The band sits at the edge of the mmWave region of the radio spectrum (30 GHz to 300 GHz) and offers a huge bandwidth where data rates of up to 10 Gb/s can be supported.

The very first international discussions on the desired goals for 5G brought forward many diverse ideas. One was this leap in data speeds to 10 Gb/s. The high data speed drove the need for very wide RF channels. This in turn directed everyone’s attention to look to bands above 6 GHz, where such wide RF channels might more readily be found. Samsung was one of the first companies to suggest 28 GHz on the basis that it looked possible to get global alignment. Everyone could see the advantage for consumers of a global allocation that would enable global scale economies and global roaming.

Such a huge data rate was headline grabbing and played well in the popular media. The supply industry became excited by the opportunity to develop components for these new very high frequency mobile bands. In 2014 the New York University hosted an influential technical workshop (the first of the “The Brooklyne 5G Summits”) that harnessed this excitement and helped forge an effective industry lobby for spectrum at 28 GHz and mmWave bands more generally.

New York University – A world Centre of Excellence for mmWave research

During this first Brooklyn 5G Summit the adverse impact on mobile coverage from using such high frequencies was hardly mentioned. It did not fit the narrative of the emerging industry consensus. Yet the mobile industry’s very foundation is that people can use their mobiles anywhere they are likely to be. That demands wide-area national coverage. The market requirement for mobile wide-area coverage was getting buried under the excitement for data speeds up to 10 Gb/s. The industry were losing the plot.

In the run-up to the ITU World Radio Conference in 2015 (WRC15) the bandwagon behind a global allocation at 28 GHz had gathered enormous momentum within the industry and was backed by a number of Governments, including the USA.

By 2015 it is no exageration to say that 5G had become exclusively synonymous with super hot spots delivering data speeds of up to 10 GB/s and using the 28 GHz band.

It left a number of mobile experts sceptical about the direction 5G was taking. Nobody was against 10 GB/s hot spots using mm-Wave bands but that alone was not going to be transformational. But these views had been marginalised by 2015.

This was the backdrop to the much anticipated ITU World Radio Conference held in Geneva in 2015. However, the mobile industry was not the only industry sector with its eyes on the 28 GHz band. In Europe the satellite industry also had ambitions for the same band. It was very important for their future development. At the ITU Word Radio Conference in 2015 the European Regulators took the side of the satellite industry. The European mobile industry lost this critical battle. They left the conference with no obvious spectrum band in which to roll out new 5G technology under standardisation.

The EU Commission had invested a lot of capital in Europe being a leader in 5G. The outcome of WRC15 confirmed for EU Officials their preferred route to 5G leadership through a focus on new 5G “applications” and particularly the use of more advanced communications by the vertical industries such as transport, health etc. In support of this they tabled a draft measure for the EU to harmonise the use of 700 MHz since most of these new applications needed national coverage whilst only demanding modest data rates.

At this point in time Europe had lost the plot. The 5G technology being developed had no suitable band to roll it out in and the spectrum band at 700 MHz being harmonised across the EU had no new technology being developed for it.

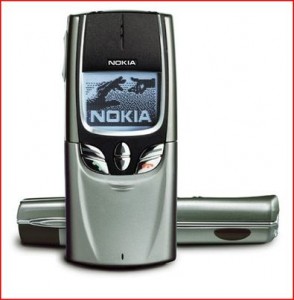

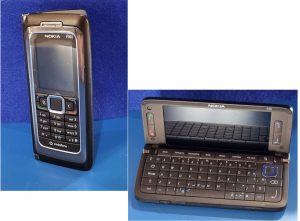

The large system vendors, such as Nokia and Ericsson, were angry at this outcome and furiously lobbied the Commission to do something about it. The Commission could see no ready solution. They tasked the Radio Spectrum Policy Group (an advisory group comprising national regulators) to study the problem and report back by 2019. But there was even less enthusiasm amongst regulators to do anything. The issue had been effectively kicked into the long grass. The 5G initiative had derailed in Europe and covered over by a fig leaf of “5G services” that for the most part would be running over 4G network and WiFi.

Whilst many in the industry realised the 5G initiative in Europe had been derailed by WRC15, few people in Europe fully grasped that no effective mechanism existed to solve the problem on the necessary timescale. Many still believed that the next ITU World Radio Conference in 2019 (WRC 19) would be an opportunity for a re-match of the fight over 28 GHz. It sustained hostilities between the European mobile and satellite industries in the 5G PPP infrastructure Group and its Working Group on Spectrum. The result was that the Working Group (usually referred to as WG-Spectrum) had become dysfunctional and unable to articulate a common industry view on spectrum.

In December 2015 Prof Rahim Tafazolli, Head of the University of Surrey 5G IC was in Brussels for a progress meeting of an EU funded Horizon 2020 project called Euro-5G. The intended purpose of Euro-5G was to help coordinate of 5G research activities and provide a gap analysis in support of EU officials. One of Rahim’s roles in the project was to contribute to the Spectrum Working Group of 5G Infrastructure Association (5G PPP) and there was certainly a yawning gap in finding spectrum for 5G. Rahim decided something needed to be done. The other partner in this activity was Terje Tjelta representing Telenor. Unknown to me, Rahim proposed that I should represent him on Euro-5G in order to find a solution to this 5G spectrum logjam.

Prof Rahim Tafazolli – University of Surrey 5G IC

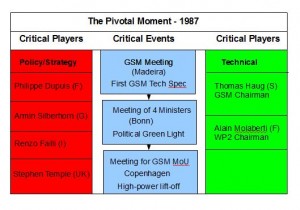

He assured his European colleagues that if anyone could find a solution it was me. My success in getting GSM off the ground 20 year earlier with the GSM Memorandum of Understanding is recognised as one of the early milestones of global cellular mobile history but that was a very different world.

Terje had in mind to put himself forward to Chair WG-Spectrum. He had infinite patience and was going to need every bit of it. I had the institutional memory and know-how of why GSM had been so successful. It was a good combination. Rahim’s proposal for my inclusion in Euro-5G was welcomed.

Terje Tjelta – Telenor

The first I heard of this was after Rahim got back from Brussels. I had a rough idea what the problem was but it seemed then to be implausible that I could do anything about it. Most of the levers I had used in the days of GSM had long since been jettisoned in the rush to liberal market economics. Some new approach would be needed.

The first challenge was to get WG-Spectrum to actually meet. Such was the antagonism between its mobile and satellite industry members that nobody could see the point of a physical meetings. Such a face-to-face meeting was a vital first step in re-establishing trust. It took nearly two months to get this first physical meeting set up in Brussels. The support of the EU Commission official, Ari Sorsaniemi, who represented the Commission on the Working Group was indispensable. In fact, without his encouragement and sensible interventions at critical moments, the initiative might have been crushed by the very effective lobbying efforts of the satellite interests.

Ari Sorsaniemi – EU Commission

Terje and I spent hours on the phone discussing how to manage this first face-to-face meeting. It was a one-shot opportunity. With the tactics mutually agreed my task was to prepare the meeting papers. I spent weeks working on a paper to shine a light on how spectrum management worked. It was byzantine. Nothing linked the progress of a new generation of technology with the release of a new spectrum band. The two worlds had become uncoupled. The industry seemed to be looking to the next ITU Word Radio Conference in 2019 (WRC19) to provide the answer. It was sucking in everyone’s resources. But nothing coming out of WRC19 would bind national regulators to do anything immediately for 5G. The ITU only sets interference conditions that need to be met at national boundaries. Also if industry would not even know what bands were likely to be available until after the conference it made the launching of 5G by 2020 impossible. The logjam was due to the fact that it was nobody’s formal responsibility to find a solution. National Regulators had embraced a principle of technology neutrality. It was almost hallmark of good regulation in a neo-liberal economy. It meant that it was left to industry to find spectrum for 5G from amongst the spectrum they already had. But the current spectrum holdings were fragmented for competition reasons, and none of the spectrum owned by any single mobile operator could support the wide RF channels that are essential for 5G. This left Europe in a position where industry was unable to find a solution and the regulators did not see that they had an obligation to find one that was linked to the release of a new technology either. Some new mechanism was needed to get regulators to re-engage in a way that did not fundamentally clash with their regulatory philosophy.

In March 2016 Philip Marnick (Ofcom) the new chairman of the RSPG called an industry workshop in London to set out to industry their proposed work programme under his chairmanship. One of the items was to study the 5G spectrum issue. It was fairly low-keyed. A senior national regulator (not from the UK) made a surprising comment, when presenting this work item, that nobody knew what 5G was. That did not bode well in finding a rapid solution, so I caught up with him in a coffee break. He told me that the prevailing view of regulators was that 5G had been over-hyped and may never happen. They had to study the issue so as not to upset the EU Commission, but they did not see it as their job to find spectrum for a specific technology and particularly one that seemed so problematic.

Philip Marnick – Ofcom

After the coffee break Philip Marnick made a statement that gave me the first glimmer of light of a way in. He said the RSPG was not interested in industry lobbying the RSPG for a specific band (by which he meant 28 GHz) but instead to present to the RSPG what the problem was that industry was trying to solve and the RSPG would then try to see if appropriate spectrum could be found. The plan was to deliver a final report by 2019. The time scale was not unreasonable measured in “spectrum management time” but very late on the much faster “global 5G time”.

The RSPG workshop was very helpful. What exactly was the problem (or problems) 5G was setting out to solve? So far, the only question being asked was how the industry could get access to 28 GHz. Philip was re-setting the question. I got the significance of this immediately. His statement was to lead Europe to change its whole direction of 5G. Philip intention at the time was probably no more than a call for evidence and to calm down the clamour for re-running the 28 GHz battle. But in doing so he had framed the right question at the right time to slot into a solution to the problem I was bolting together for an industry/research community initiative.

Ideas had to be turned into written contributions for the face-to-face meeting in Brussels of the 5G PPP Working Group on Spectrum (WG-Spectrum). It was evident to me that nobody in the research community really understood how the current system of spectrum management worked and its limitations in solving the 5G spectrum issue. I had to get everyone onto the same page that Europe’s current spectrum management arrangements were incapable of delivering a harmonised band into the market suitable for 5G by 2020. In other words if we didn’t play our part the chances were that nobody else would.

The really big challenge was to think of an effective mechanism to get the Regulators to re-engage in finding spectrum for a new technology in a way that did not involve them in doing it by regulatory means. It had to be “a voluntary approach” that secured market power through consensus and momentum. My solution was to come up with a new concept of “5G Pioneer Bands”. The devil (or in this case the angel) was in the detail of how I defined what a “pioneer band” was.

My idea was to place a first “stake in the ground” for the choice of band we would use in 5G research and Test Beds that appeared the most likely to be used in the first commercial deployment in the first European country. That is where the word “pioneer” comes from. It is the intimate coupling of the fruits of research with the very first deployment in the very first country or countries. The objective was then to identify a band that maximised the number of countries who felt able to also support the band for 5G commercial use in their countries. Discovering this first band could only come out of a dialogue between the industry saying what was desirable (to solve the problem) and regulators saying what could be made available by 2020. The criterion of success was to have enough countries supporting this first stake in the ground (the pioneer band) to ensure a size of market delivering the necessary early scale economies. Not requiring every EU country to have to agree was critical as it made the problem less political and more soluble. All that mattered was the cumulative size of market by 2020 being big enough to attract viable commercial interest. Once such a bandwagon could be got going, then other countries would come under pressure to join so as not to be left out. This would be helped along by using the band in research and Test Beds, as it would create 5G equipment facts on the ground and therefore make it the easiest band to use. This completed a virtuous circle.

That was my “5G Pioneer Band” concept and plan.

The “5G pioneer band” band approach solved so many problems at the same time:

- It gave the industry research community a legitimate reason to talk about the sensitive subject of very specific bands for early 5G commercial deployment by linking this to the same spectrum to be used for our own research and Test Beds. The use of specific bands had become so politically and commercially sensitive over the years that meaningful discussion that linked a technology to a band had been actively discouraged in research and standards making communities.

- Focussing on the pioneer bands took the temporary focus off the ITU agenda of all the possible future mobile bands. This was essential as it was no use having lots of potential future mobile bands if it proved impossible to find a mobile band to get 5G off the ground in the first place. Often in fast moving technology an opportunity delayed is an opportunity lost.

- The pioneer band approach created a counter-balance to the hitherto runaway mobile world of band proliferation. Some 44 bands emerged in the 4G standards period causing massive design challenges that were proving impossible to entirely resolve. Only a fraction of these bands appeared in popular smartphones. Coming up with another dozen 5G bands seemed a bad idea in the circumstances. We needed a focus on just a few 5G bands to maximise the chance of them appearing in popular global smart phones early and this would improve early scale economies and roaming opportunities.

- It improved the efficiency of the 5G research by eliminating the need for a re-banding development phase. The results of Test Beds and trails would be directly applicable to the planning of commercial services as the spectrum band would be identical.

WG-Spectrum were ready to give the approach a try.

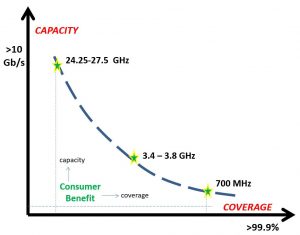

The next critical step was to get industry agreement on the problem we were trying to solve. I prepared a paper to demonstrate that one single spectrum band could not do the job. It was impossible to find one band that could deliver huge capacity (high data speeds) and pervasive national coverage at the same time. Going all out to find a band that maximised one would automatically lead to the other being minimised. The consequence for mobile coverage of using the new mm-wave bands was first brought to my attention in a presentation from Andy Sutton of EE at a University of Surrey 5G IC Technical

Andy Sutton – EE

Workshop. This was an excellent example of the 5G IC industry/academia cooperation that helped direct academic thinking towards the real problems industry faced. The trick was to find a way of showing that at least three bands were needed and the necessary relationship with each other that could be understood at a glance. WG-Spectrum colleagues helped me shape an effective illustration:

The illustration that drove the 5G pioneer three-band solution

The illustration was very successful as a framework for bringing everyone together very quickly to identify three spectrum bands. The 700 MHz band the Commission were pushing slotted-in very nicely to meet the need for pervasive coverage. The choice for a very high capacity band lay between 26 GHz or 32 GHz. (That choice led to a huge row within WG-Spectrum but more of that later). My own agenda was to push an intermediate band (3.6 GHz) that would offer an ideal compromise between capacity and coverage. The capacity increase would be a significant advance but not as large as 26 or 32 GHz could deliver and the mobile coverage would still be extensive (say all cities and towns) but not as extensive as the national coverage that 700 MHz could readily deliver. It would enable urban mobile broadband coverage at data rates in the range 1-3 Gb/s and facilitate the vision of a Gb/s society. (Note: The proviso for success, however, is that it would need to be accompanied by a regulatory framework that allowed 100 MHz wide RF channels to emerge in the band and a more supportive regulatory environment for maximising coverage from dense small cell networks).

Just three well chosen bands would offer the very best combination of capacity and coverage for the least number of bands. The solution seems so obvious today but in 2016 it took a dispassionate review of “the problem to be solved” to allow a more encompassing solution to emerge. It was Europe’s Eureka moment.

The 5G pioneer band initiative changed very quickly from an almost solo effort on my part to a team effort. Rauno Ruismaki from Nokia stepped in to draft the section on the 26 versus 33 GHz. His technical expertise was considerably greater than mine. I focussed on drafting the section on 3.6 GHz. It was the 5G band that Rahim favoured for dense small cell networks. It also had industrial support. Dr Wen Tong had mentioned to me at a Huawei event in Munich in 2014 that he thought 5G implementation might be faster at 3.6 GHz than 28 GHz. Nokia also supported it. Everyone in WG-Spectrum was keen to bring 700 MHz into the 5G spectrum story-line. This was essential for a comprehensive approach to up-grading Europe’s future mobile broadband infrastructure. The chairman Terje Tjelta and our rapporteur to the RSPG for this initiative, Ulrich Rehfuess from Nokia, provided the leadership and strong support for us to make progress in WG-Spectrum on a text acceptable to everyone.

Ulrich Rehfuess and Rauno Ruismaki from Nokia Networks

WG-Spectrum was a very polarised group to start with between mobile and satellite interests. The 26 GHz versus 32 GHz choice re-opened the divergence. The mobile interests quickly aligned behind three 5G pioneer bands of 700 MHz, 3.6 GHz and 26 GHz and with the exception of SIP from Italy. Italy had a problem with 26 GHz and preferred 32 GHz. The satellite interests were adamant that the choice could only be 32 GHz. The 26 GHz band (just adjacent to 28 GHz) was important to the European satellite industry. Satellites have such high visibility that massive capacity translates almost directly into a demand for massive bandwidth. An impasse in WG-Spectrum quickly emerged that could not be resolved. It was more efficient just to let the RSPG to finally settle the matter. Ulrich Rehfuess took on the unenviable task of finding a text that balanced on a knife edge the pros and cons of the two options.

It is one thing to have the right ideas but quite another to communicate them effectively into another body that sees things through a quite different prism. I copied every draft version to David Hendon from Ofcom who helped me shape the 5G PPP papers into a form that he and his Ofcom colleagues could best use to build the wider consensus. David also happened to be the Chairman of the University of Surrey 5G IC Strategy Advisory Board and I was the Technical Secretary. The resulting “working level” close cooperation in solving the 5G spectrum blockage problem proved the value of the 5G IC in pulling around the same table the entire UK mobile eco-system.

David Hendon – Ofcom

The hard slog of satisfying everyone’s drafting points was finally over (and at times it was really hard), the papers had been pre-cleared with the Ofcom RSPG delegates and I was 5 minutes away from pressing the “send key” to dispatch it to the RSPG 5G Working Group when, out of the blue, I received an e-mail from a senior Commission Official prohibiting us from sending the contribution. It went against EU policy. The EU Official who normally followed the WG-Spectrum, Ari Sorsaniemi, was on mission and not contactable. The concern was that EU policy was to focus on 5G applications and something aimed at advancing 5G networks would be sending out mixed messages. We were not to send it.

If the documents were not sent, we would miss the critical meeting of the RSPG 5G working group meeting that was only days away. The Commission Official who was our friend and mentor was on a mission. I was on my own. Fortunately, this had happened to me once before when I was a senior Civil Servant. Lord Young arrived in the DTI a few days before I was to fly out to Copenhagen to get the now famous GSM Memorandum of Understanding signed. He forbade me to go and wanted a review of our cellular radio policy that would take months. It was no time for exasperation, tantrums or throwing myself off a high building in a deep depression. The only way was a respectful explanatory draft with a very balanced argument that would allow “the boss” to arrive at his own view to lift the veto. Within two e-mail exchanges the senior Commission Official was happy with my explanation. I said that spectrum was a long lead item and now was when we needed to help Regulators with the right technical advice. It was also highly unlikely to catch the attention of the media. The paper went forward with his blessing. (Note: in theory the 5G PPP is independent of the EU Commission but in practice they are well respected as a very helpful force that holds everything together for the wider good).

The 5G pioneer band seed had germinated in the 5G PPP incubator and it would now fall to others to nature it to fruition. My part was over.

From that point on the action moved to the RSPG. Philip Marnick, its chairman set a cracking pace to get RSPG consensus behind the 5G pioneer bands. He was under pressure from the EU Commission on time-scales. They wanted the RSPG input in time to publish their EU’s 5G Action Plan by September of 2016. A working group under the chairmanship of Bo Andersson, Chief Economist at the Swedish National Post & Telecom Authority was established. Philip Marnick made it known that he wanted a draft Opinion from the group for RSPG to adopt in a matter of weeks rather than months. So the work of the Group focused on what could be said before the end of 2016.

The 700 MHz band was already a done deal as the Commission had taken action to ensure it was available throughout Europe in the required timescale, but it was now openly acknowledged that this band on its own would have no impact on European 5G at all. To try for agreement on the 3.6 GHz band was the obvious next step.

David Hendon and Joe Butler from Ofcom, working closely with Eric Fournier from the French regulator ANFR helped to focus the Group’s attention on the 3.6 GHz band and very quickly it emerged that there was ready consensus among the regulators that this band should be identified as one of the Pioneer bands very quickly. Different countries had different levels of availability of parts of the band, but nevertheless the imperative of having several 100 MHz carriers available in each country led to the whole of the band 3.4 to 3.8 GHz being identified. The draft Opinion went out to public consultation. This work hugely boosted the importance of 3.6 GHz for 5G in Europe. They not only doubled the recommended bandwidth to the entire 3.4-3.8 GHz range (adding the band above the 5G PPP choice of 3.4-3.6 GHz) but suggested it was the range where Europe could secure a global lead. That was a very powerful signal.

Joe Butler – Ofcom

At this point Philip Marnick made another decisive intervention. He forced his Ofcom colleagues to really bottom out the arguments between the choice of 26 GHz and 32 GHz as the third pioneer band. 28 GHz was not going to be available in Europe because of heavy existing use in the Region by satellite operators. 26 GHz could be, but was heavily used for fixed links in many countries. 32 GHz on the other hand was less heavily used in Europe, although in some countries there were major impediments. In the UK for example, the 32 GHz band had been auctioned and the initial term of the licences extended well past when it would be needed for 5G. But as well as that, there were other considerations. It was possible to imagine that devices could be made that could be tuned across both the 26 GHz and 28 GHz band, but the same wasn’t true for 32 GHz where a 1 GHz “Quiet band” sat between the 28 GHz and 32 GHz bands. Building filters to protect this band in practical devices would be very expensive and cumbersome. Furthermore, from a survey of the opinions of some key regulators across the world, Ofcom reached the view that it was more likely that 26 GHz would emerge as a global band and there was also a real risk that if Europe chose the 32 GHz band, it would find itself in a backwater and unable to source network and user equipment.

Philip led a process in Ofcom to decide what the UK would prefer and gradually it emerged clearly that 26 GHz, despite the many services in the UK that would have to be moved, was the preferable choice.

Joe Butler took this conclusion to a meeting of the RSPG 5G group in Dublin late July 2016 and for the first time the wider group thought about the wider issues. The issue was discussed again at the next meeting of the RSPG 5G group in London after the summer break. A fragile consensus emerged. 26 GHz was supported by many administrations but there remained some who were either unhappy or the delegates had not been mandated to support this conclusion. The drafting of the revised Opinion was tricky and helped immeasurably by the skilled English-language drafting of Eric Fournier in particular, with his drafting onto a PC which was projected onto a screen so the whole group could see and participate. By the end of the meeting, there was a text that could go to the Plenary and further consensus-building took place before the RSPG Plenary meeting, so that the Plenary was able to agree on the choice of 26 GHz after some further appropriate safeguard wording had been included and the final RSPG Opinion was ready.

The Commission were delighted with the outcome. They smoothly picked up the 5G pioneer band choices when their 5G Action Plan was published on the 14th September under the heading “Unlocking bottlenecks: making 5G radio spectrum available”.

EU Action Plan promoting 5G deployment in Europe

The RSPG Opinion on the 5G pioneer bands in final form was published after the EU 5G Action Plan on the 9th November 2016.

The three 5G pioneer bands were cemented into Europe’s 5G approach:

Low band 700 MHz,

Middle band 3.4 – 3.8 GHz (3.6 GHz band), and

High band 24.25 – 27.5 GHz (26 GHz band).

Other parts of the world penalised themselves by asking themselves the wrong question – the 5G band is 28 GHz now what can I do with it? The answer is: not a lot – only hot spots and wireless local loop – a very limited vision. European industry and academia, nudged by the RSPG Chairman, analysed first what the problem (or problems) 5G was being designed to solve. The right answer was that 5G needed to do far more than just deliver very high capacity hot spots (or wireless local loop):

- The ubiquity of the Internet of Things is to be underpinned by a network engineered at 700 MHz to offer very reliable near universal connectivity and cope with billions of devices. The 700 MHz network with such pervasive coverage will also be central to 5G (even if it continues to be based upon LTE technology) by becoming the 5G control plane of choice. I sometimes refer to this as the “home page” of mobile spectrum bands.

- The big mobile broadband transformation will be achieved by mobile network operators rolling out carpets of dense small networks at 3.6 GHz to cover our cities and towns to lift the headroom of mobile broadband networks to cope with another 20 years of solid growth of capacity demand and faster data speeds as well as delivering very much lower latency. Massive MiMo shaping narrow high-gain beams would allow coverage of suburban areas more economically.

Massive MiMo Antenna being installed by Huawei

- Getting 3.6 GHz indoors would also be an important improvement of indoor coverage/capacity. The mobilisation of such high performing networks that offer seamless connectivity outdoors and indoors will make a significant contribution to national productivity.

- On top of this would be strategically placed super-hot spots to meet huge peak demands at football matches, other locations of very high footfall and within factories of the future. The problems of finding a global spectrum band for this has been neatly resolved by having two bands, 26 GHz and 28 GHz close enough together so that a single tunable component handles both.

The direction of 5G in Europe had been re-set towards a far more powerful infrastructure up-grade delivering considerably more for businesses and consumers.

The “5G pioneer band” initiative achieved four specific things:

- It broke the log jam in a way that allowed consensus on a good choice of 5G bands to be achieved. The time from “nothing” to “European consensus” on an issue of such importance took only 6 months, which must be a record in the world of European spectrum management.

- It brought “coverage” back centre stage in driving the choice of spectrum bands, which is vital to sustain “mobility”…the very bedrock of a mobile service and its contribution to productivity. It has achieved this whilst retaining the thrust towards considerably high data rates and much lower latency. It has resulted in a far superior alignment of spectrum bands with market needs.

- It reversed the mad dash towards mobile band proliferation. The focus on the minimum number of bands essential to solve the problems will lead to more efficient smartphones and networks. It reversed the mindless pre-2015 mobile industry dash to collect mobile bands like collecting postage stamps.

- It improved the efficiency of European 5G wireless research projects.

All of this was achieved by somebody framing the right question at the right time, somebody listening with the institutional memory and know-how of how to shape the solution and for it to be picked-up and supported by capable leadership in Ofcom, the EU Commission, European system vendors and MNO’s and not least, from my viewpoint, the University of Surrey 5G IC.

Other material on European cellular spectrum history:

GSM Spectrum – a political history

A week in Paris – How, in 1980, Europe’s spectrum managers planted the first seed for a harmonised pan European cellular mobile spectrum band at 900 MHz